Last year, I spent many delightful hours studying the Bologna Cope at the Museo Civico Medievale in Bologna, Italy. This Opus anglicanum cope was made in England between AD 1310 and 1320. The cope was also displayed at the epic Opus anglicanum exhibition in the V&A in 2016/2017. Although the cope is missing its hood, morse and orphreys, it measures an impressive 149 x 326 cm. Instead of being embroidered on an expensive silk fabric, like the Vatican Cope we saw last week, the embroidery on the Bologna Cope covers every centimetre (!) of the linen embroidery fabric. Let me introduce you to this impressive piece of medieval goldwork embroidery.

The design of the Opus anglicanum cope is divided into several bands. The bottom row contains scenes from the Life of Mary & Jesus under Gothic arches. In the triangular areas between the arches, angels play various musical instruments. The smaller band above contains the busts of male saints. The taller band above that one contains more scenes from the Life of Mary & Jesus, followed by a band with busts of male saints again. The small semi-circle left at the top is filled with two censing angels flanking the now missing cope hood.

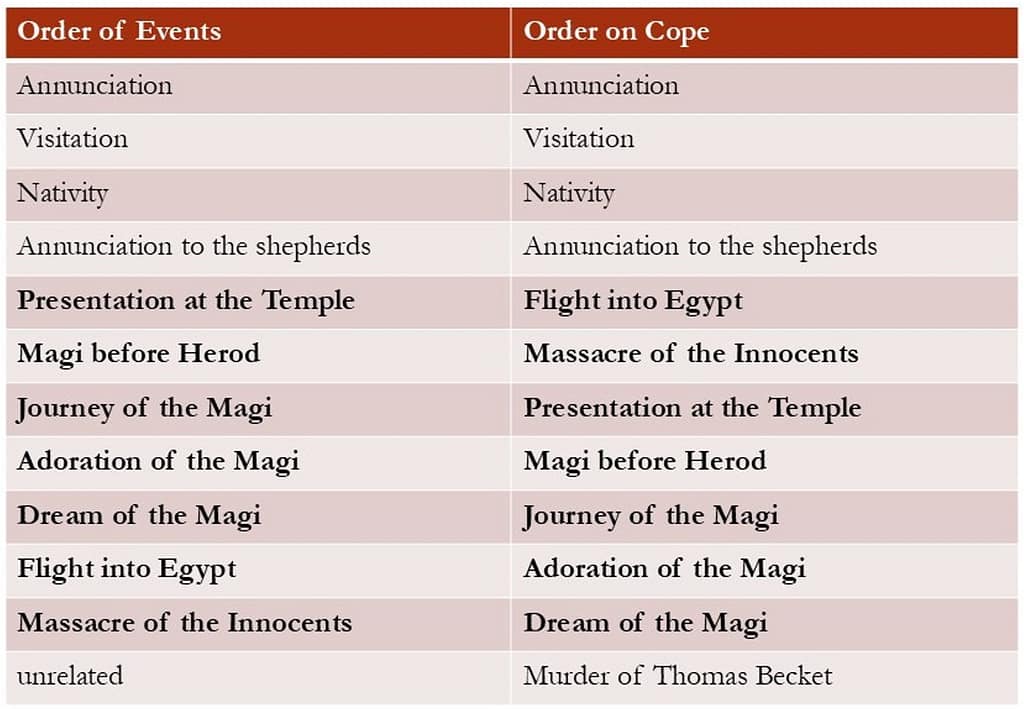

If you have been following my blog for a while, you know that medieval art always has deeper meanings. Nothing is depicted incidentally. This is undoubtedly the case for this Opus anglicanum cope. The order of the embroidered scenes in the bottom row does not follow the order of events as told in the Bible. Why is that? There’s more than one way to ‘read’ this cope.

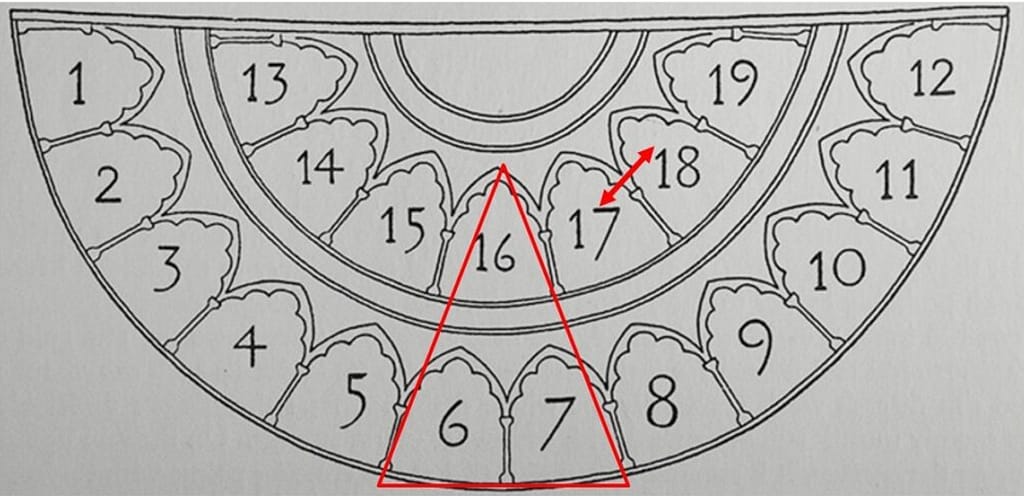

The red triangle above represents the part on the back of the Cope that is relatively flat on the wearer’s back. Scene 16 shows the Crucifixion, the central theme of the liturgy. This scene is ‘supported’ by scenes 6 and 7 when the cope is read from bottom to top. So what’s in scenes 6 and 7, and how do they relate to the Crucifixion?

Scene 6 shows the Massacre of the Innocents. At the behest of Herod the Great, all male infants are killed in Bethlehem—a very bloody event, from which Jesus is saved as he flew in time to Egypt with his parents. Scene 7 shows the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple. Mary and Joseph go to the Temple in Jerusalem 40 days after Jesus’ birth to sacrifice a pair of doves. This scene usually shows Jesus being handed over or standing on an altar. Both scenes contain key elements of the Redemption through the Crucifixion, which is celebrated in the Holy Communion.

But this is not the only switch. Scenes 17 and 18 in the second major row are also swapped. Why is that? The scenes closer to the central Crucifixion scene would be easier to read when the cope is worn. So, swapping a more important scene for a lesser one makes sense. In this case, the Harrowing of Hell was swapped with the more important Resurrection.

One of the things that intrigues me is how many onlookers would have been able to read these theological riddles. Had the average parishioner enough theological knowledge to pick up on these things? Was it only aimed at the clergy? If you are a Christian yourself, would you have been able to notice and explain the switched scenes?

From the above, it becomes clear that the design of the Bologna Cope was carefully planned. But how was the Opus anglicanum embroidery executed, and what can it tell us about the tools used? As you can see from the pictures, the silken split stitches are tiny. To achieve such miniature stitches, the embroiderer needed an equally fine needle. Sadly, none of these needles have survived in the archaeological record. Seeing the finished embroidery, they must at least have equalled our #10 needles or even our #12s. Imagine making these fine needles without today’s machines!

The above picture also suggests that the design drawing was (at least partially) drawn freehand onto the embroidery fabric. See the corrected line in the calf of one of the legs. This means the linen fabric needed to be framed up before the draughtsperson could go to work. Did this person work from memory, or were smaller sketches scaled up? I so want to be able to travel back in time!

We know this draughtsperson did not have the final word—the embroiderer did. Initially, the draughtsperson had drawn a complicated diaper pattern for each scene’s golden background. The embroiderer never executed this. Instead, maybe to speed up the process, the embroiderer opted for a simple chevron pattern. Needle and thread are clearly more powerful than brush and ink :).

Literature

Browne, C., Davies, G., Michael, M.A. (Eds.), 2016. English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Michael, M.A. (Ed.), 2022. The Bologna Cope: Patronage, iconography, history and conservation. Studies in English medieval embroidery II. Harvey Miller, London.

0 Comments